In ancient Greek the name of this mineral is translated as "being alone, living alone." In 1829 German mineralogist Johann Breitgaupt called this previously unknown new stone based on the isolation of its crystals from each other. Surprisingly, when some time later, radioactive thorium and uranium were found in its composition, the infernal name of the stone was again confirmed.

Monazite was first discovered three years earlier in the Southern Urals in the Ilmensky Mountains, near the town of Miass, by another German mineralogist, Johannes Menge, who mistook the stone for zircon. Later, to confirm his conjectures, the scientist sent samples to his colleagues Gustav Rosa and Johann Breitgaupt for examination.

Against the background of the general interest in radioactive materials, monazite began to be mined as a thorium source in the USSR in the 1930s. Large deposits of the mineral at that time were concentrated in two locations: at the Tarak deposit in Siberia, and in the Sverdlovsk Region, in the settlement of Ozernoye. There, monazite was found not only in the form of separate crystals, but also in the form of alluvial sands. After valuable components were extracted from them, large volumes of already depleted, but still containing thorium, were left in the form of free access dumps. Heaps of construction material could not leave the inhabitants of nearby settlements indifferent, so the most enterprising began to scatter it for household needs. When studies were conducted in these areas sixty years later, it was found that residents received elevated doses of radiation. The settlements, consequently, had to be decontaminated.

As a matter of fact, monazite radioactivity also found its application during the Second World War. The Germans poured monazite sand on the ground during the installation of "Topfmine" type mines, which contain almost no metal parts and cannot be detected by ordinary mine detectors. This helped detect the mine easily during mine clearance.

After mining operations ceased, it was decided to collect the stockpile of monazite in one place near Krasnoufimsk. Special wooden barns were erected to store the dangerous material. Thousands of tons of raw materials were stored there for more than 60 years, until the authorities of the Sverdlovsk Region drew attention to the situation in the 1990s.

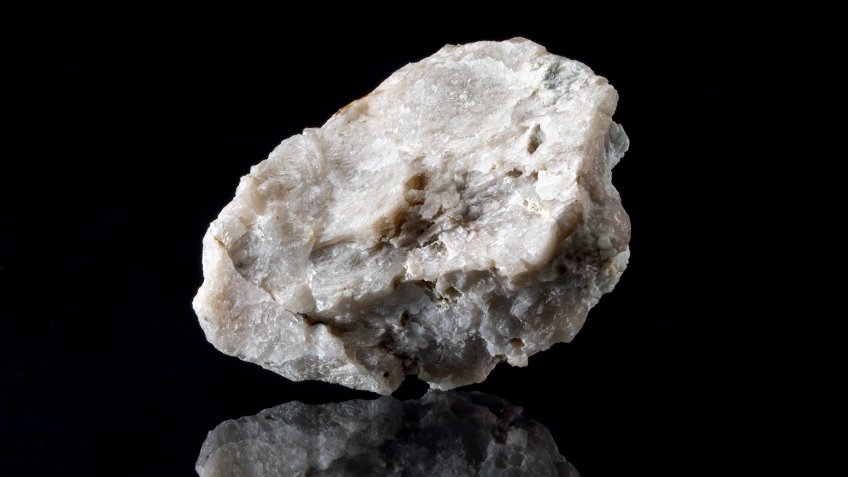

They decided to use the stone chips to extract rare-earth metals, which were already quite high in price at the time. The idea of creating an enterprise to process this waste and extract useful components seemed commercially very promising. The brown mineral, unsightly at the first glance, contains not only radioactive elements, but also rare-earth metals that are indispensable for production of hybrid automobiles, wind energy turbines, and computers in the 21st century. It turned out that monazite contains more than 50% of oxides of such elements as scandium, yttrium, and cerium. However, nothing came out of this idea.

Last year, since Russia had not invented safe technology for processing of monazite sand, it was decided to export it to China, where appropriate facilities are located. The export plans were hindered by the closed borders due to the pandemic. Monazite packed in special containers is waiting for its time to come.

It would seem that the stone cannot be exhibited in museums because of its specific properties. However, the samples of this mineral are presented, for example, in the Mining Museum of St. Petersburg. Here, before any minerals are put on display, they are subjected to radiological control to make sure they meet the safety standards. This holds true for all exhibits. Several samples of monazite pose no danger, as opposed to several tons.

Interestingly enough, the overall radiation levels inside of the Mining Museum are much lower than outside, on the streets of the city.

Translated by Diego Monterrey, for Northwest Forpost.