It is hardly possible to guess an exact number of museums - an estimate would be over 100,000 globally. As for exhibits on display, there must be tens of billions of them. While they are all to some extent interesting, some items are so unique that people travel long distances to glance at them.

St. Petersburg Mining Museum has several such showpieces:

- Sikhote-Alin meteorite weighing 450 kg,

- the world's largest preserved chunk of Ural malachite,

- the skeleton of a cave bear and skulls of fossil rhinoceros,

- a palm forged from a single-piece rail,

- and other extraordinary specimens.

In 1773, Empress Catherine the Great signed a decree on establishing the first in Russia higher technical school: the Mining School. She also ordered the Mineralogical Room to be set up on its premises. Already in 1777, on visiting the Museum, Gustav III, King of Sweden, became so delighted with what he saw that he gifted 202 samples of Swedish ores, salts, and rocks.

The number of exhibits kept growing. Under a decree of Catherine II, all owners of mining enterprises and deposits in Russia were obliged to send the most outstanding samples of minerals, ores and factory products to the Museum. Besides, artefacts were purchased at international exhibitions and obtained from private collections of reigning dynasties and researchers - both Russian and foreign.

In less than 20 years, what was once a room in the university became officially recognised as a museum. Nowadays, the Museum houses over 240,000 items. Some of them are truly unique and have a history behind them: world records and fascinating provenance.

Block of malachite

A malachite block weighing a ton and a half was extracted from below the surface almost 250 years ago, not far from where nowadays the city of Ekaterinburg stands. The lump of the mineral could have been even more massive. However, due to technical difficulties, the chunk could not pass through the deposit's narrow openings. Consequently, mine workers had to gradually cut off small pieces of the rock until the malachite block was pushed out of the working. The lump of the most sought-after gem of the 18th century was transported to St. Petersburg and gifted to Catherine the Great. The Empress of Russia kept the rock in her private collection for some time. Then she handed the sample over to the Mining Museum, St. Petersburg.

The unique discovery is acknowledged as the world's largest chunk of Ural malachite amongst those preserved. There is a high degree of certainty it will remain this way forever, as the mineral is no longer extracted. Russian deposits are nearly depleted, whereas specimens mined in Africa are often of much lower quality. The price of the rare and precious exhibit is estimated at several million US dollars.

Items from the House of Fabergé

The Mining Museum showcases twenty exclusive items of the House of Fabergé. Yet if not for the favourability of the imperial family, the world-famous jeweller might not have been that successful. It started with Tsar Alexander III's commission to make an Easter egg as a gift for his wife. The present left an indelible impression on the Empress Maria Feodorovna, and soon the House of Fabergé was bestowed with the title "Goldsmith by special appointment to the Imperial Crown". The tradition of the Tsar giving his Empress a surprise Easter egg by Carl Fabergé continued. Later, it was extended to making gifts to other family members and foreign guests.

Along with the famous Easter eggs, souvenirs made of ornamental stones and precious minerals are considered the hallmark of Carl Fabergé. Among the Mining Museum's exhibits is a grey elephant from Kalkan jasper, which belonged to the Grand Duchess Elizabeth Mavrikievna of Russia, wife of the Grand Duke Konstantin Konstantinovich. Xenia Alexandrovna, sister of Nicholas II, the last Emperor of All Russia, owned parrot figurines and a box of shell-imitating agates.

"For connoisseurs of Carl Fabergé's works, it's a great piece of luck to even set their eyes on these rarities", notes Riana Benko from Fabergé Research Site. Such items are often part of private collections, like those of the Queen of the UK and Prince of Monaco. In 2004, a Russian admirer of Fabergé Imperial eggs acquired 9 of them in New York for $120 million and brought them back to Russia. Now they are housed in the private-owned Fabergé Museum in St. Petersburg.

Sikhote-Alin giant meteorite

The winter of 1947 saw the fall of a massive meteorite in the Ussuri Taiga. It broke into pieces on entering the atmosphere and turned into a meteor shower. The fragments were scattered over an area of 35 km². As often happens when an asteroid falls, eye-witnesses mentioned a brightly glowing fireball fast approaching Earth, which was followed by a loud crash. The impact zone was found to have been covered with 106 craters ranging from 1 to 28 metres in diameter, with the largest being 6 metres deep.

The meteorite remnants were studied by the country's leading scientists. One of the ten most enormous fragments - a rock weighing 450kg - is now stored at the Mining Museum.

Cave bear

The Mining Museum's palaeontological collection lets the visitors feel as if they were inside the Jurassic Park movie. Looking at the skeletons of ancient vertebrates, varying from agnathas and fish to mammals, one can compare their sizes to today's flora and fauna. The Hall of Quaternary Geology is particularly fascinating to explore since this was when humans evolved.

The exposition's notable items include some primitive tools and a model of a hunting scene. Nonetheless, the most spectacular exhibit is a rearing onto its hind legs cave bear, which shows its teeth. It is one of the largest mammals of that period. Luckily for us, its last hunt was approximately 24,000 years ago.

Adult males of the species weighed up to 500 kilograms whilst females about half of that. Quite surprising is that these large animals were predominantly vegetarians - they fed on fruits, berries and roots, rarely on small animals and carrion.

Mount Blagodat in miniature

As noted earlier, in addition to samples of minerals and ores, mine owners also had to provide their newest factory products to the Museum. Sometimes, mine operators and managers, who wished to please the Emperor and illustrate their progress, showed initiative. They manufactured models of best deposits and handed them in as well. The model of Mount Blagodat is the jewel in the crown of the Mining Museum's collection.

In the mid-19th century, the richest deposits of high-quality magnetic iron ore were found in Sverdlovsk Oblast, Ural. That very fact was perceived as an act of God's grace, which influenced the place's name. The reserves discovered there played a pivotal role in the development of ferrous metallurgy in Russia. They were also the primary source of raw materials for the factories set up at Mount Blagodat. The deposits on the territory are exceptional and not because of their importance to the industry. There is no other location in the whole world where an extensive ore deposit would lie on top of a mountain.

This model is a miniature of how the open-pit quarry at Mount Blagodat looked like in the 19th century. It was brought to the Museum in 1902 by Nikolay Iossa, then director of the Mining Institute, who had earlier gone on a joint trip to the Ural with Dmitri Mendeleev.

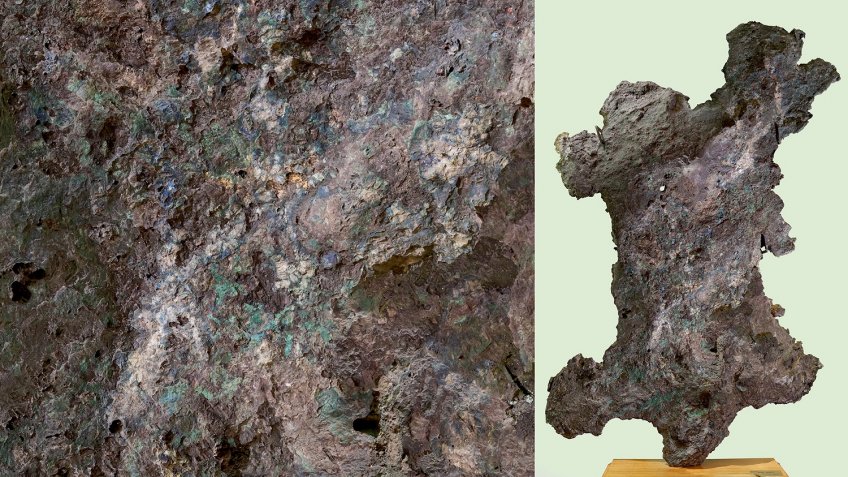

Copper skin

Emperor Alexander II was known as a votary of hunting. He loved gunning for deer, foxes, hares and grouse, but particularly favoured larger animals. The Gatchina Palace in Leningrad Oblast holds the slingshots with which the Tsar himself went hunting bears - a dangerous thing to do!

Stepan Popov was allowed to explore the steppes of Kirghizia in search of gold and ores. A savvy miner knew about Alexander II's passion, so he presented to the Tsar a copper nugget of 842 kg he had found in Kazakhstan. It is one of Russia's most giant copper nuggets ever, but the most peculiar about it is not its size but its form. The exhibit passed over to the Mining Museum by the Emperor resembles a bear pelt greatly.

In fact, the gift had a purpose. The Governing Senate claimed Popov should pay a fine of 200,000 roubles (approx. $2 mln in today's money). He hoped he would earn the Tsar's mercy thus, and while the present became a real gem of the exposition, it did not serve the original aim. The Regional Government of Omsk carried out an inventory and assessment of the second and third floors of the Bogoslovsky mining plant. Stepan Popov was put under control and was supervised from then on.

Palm of steel

The Mining Museum has indeed a lot to offer its visitors. One of the most famous of its items is nevertheless a palm of a steel rail. It was made specifically for the All-Russia Industrial and Art Exhibition of 1896 by the Novorossiysk Society of Coal, Iron and Rail Production. The enterprise was founded by John Hughes, a British mining engineer.

The product was meant to advertise the highest quality of steel, therefore working on it was entrusted to the most experienced blacksmith - Alexei Mertsalov. It was forged by hand from a single piece of open-hearth steel rail. In 2-3 weeks, the palm was ready. It was 3.5m high and weighed 325kg, with a 200-kilogram planter and the tree itself being 125kg in weight. Filipp Shkarin, a 17-year-old apprentice, took part in the process. In the 1950s, he provided a duly certified description of the work on the palm. He also confirmed it had been made from a single rail without welding individual leaves to the stem. The metal bar was heated and processed on the ordinary anvil using the method of open-die forging. Open forging was done by eye, albeit from a sketch.

This masterpiece of blacksmithing enjoyed the rapturous reception and was mentioned in numerous newspapers and magazines of the time. Once the exhibition ended, the palm, alongside other exhibits from the machine-building plant in Yuzovka, was passed to the Mining Museum. Nowadays, it is featured on the coat of arms of Donetsk Oblast. An explanation would be that Yuzovka is one of the former names of Donetsk, and that is where the plant was located.