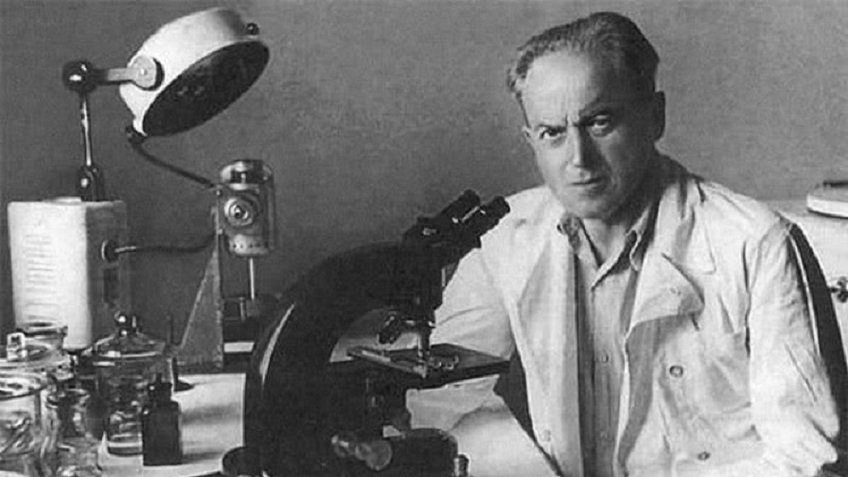

An epidemic of a mysterious disease, a previously unknown form of encephalitis, was raging in the Russian Far East. A scientist who identified its carrier is now righteously called the father of Soviet immunology. Yet, the medic was accused of spreading the deadly infection via water supply systems and declared a public enemy.

There were many similar stories at that time. Terror of 1930s-1950s, Gulag, "medical case" in 1952. Lev Zilber was arrested three times between 1930 and 1944.

The first time he, a young director of the Institute of Microbiology of Azerbaijan, was sent to Hadrut to supervise the suppression of an outbreak of plague. The cyphers decided to call it "ore" not to cause panic among the population of Nagorno-Karabakh. This disease had killed entire cities back in the Middle Ages, but how could it have emerged in the 20th century?

The story resembled an adventure detective with elements of a thriller. According to a local NKVD officer, foreign saboteurs spread the disease through the republic, opening plague-ridden corpses and cutting out hearts and livers. The scientist considered this version absurd - "in a few days you can get enough germs in a laboratory to infect hundreds of thousands of people". They took him to the cemetery so he could see the whole thing with his own eyes. The doctors were faced with a horrific sight: the tops of the already opened coffins were lifted, three out of ten corpses were missing their heads, and their organs were cut out.

In his memoirs, published in the journal "Science and Life", Zilber wrote that the solution came unexpectedly. A local teacher had told him of the area's customs, legends, and beliefs in a village. One of them thoroughly explained the mystique.

"If members of the same family die one by one, it means that the first one who died is alive and is pulling everyone to his grave. How do you know if it is true that he is alive? Bring a horse to the grave and give it oats. If it eats, he is alive in the grave. It would help if you killed him. A dead man will not drag anyone to the grave. Cut off the head, take the heart, the liver. Slice it up and give it to all the family to eat."

After this story, the corpses were burned. The entire population was moved into tents and isolated for a fortnight, and their buildings were treated with chloropicrin. The plague was eliminated.

On his return to the institute in Baku, Lev Alexandrovich determined the cause of the epidemic. He found information about plague outbreaks that had occurred many years earlier in areas neighbouring Nagorny Karabakh. In 1929, rats and mice migrated to Hadrut, bringing along the disease due to incomplete grain harvesting.

Zilber was presented with the Order of the Red Banner but did not receive the promised award until 35 years later. He was arrested and accused of spreading the plague in the Transcaucasus and attempting to infect the inhabitants of Baku with the "black death". Allegedly, the bacteria he brought with him for research was needed for another purpose. The version of foreign sabotage failed, and someone had to answer. Despite the investigators' best efforts, the scientist did not sign a single confession. He was saved only by the intervention of Maxim Gorky, to whom the younger brother of Zilber, known writer Veniamin Kaverin, author of the adventure novel "Two Captains", addressed with a request for help. Four months later, the medic was released.

"The case" was quickly forgotten, as if it did not exist. A month later, Lev Alexandrovich was awarded the title of professor and the degree of Doctor of Science at the Moscow Institute of Advanced Medical Training. He worked in several major research institutes, headed the fight against smallpox in Kazakhstan and created the first Central Virus Laboratory in the USSR.

His second arrest occurred in 1937. But it was preceded by an event that became a turning point in the history of Soviet virology.

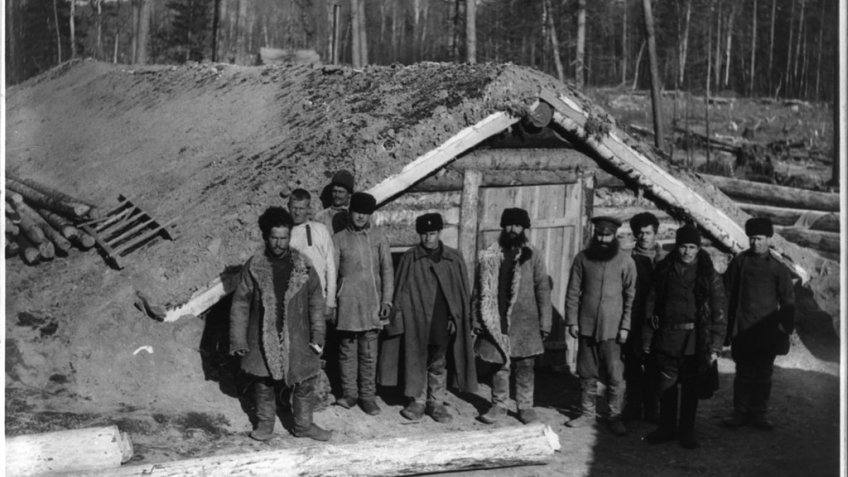

Doctors in the Far East were confronted with an unknown disease that was either fatal or seriously affected the nervous system. The region was being actively developed - ore, gold, and timber were being mined. Large army units were moved into the taiga. They were to be a support in case of Japanese aggression. The affliction was first described as far back as 1935. The scale of the scourge began to grow at an unprecedented rate with the arrival of the Red Army. Commander of the Special Far Eastern Army Marshal Blucher reported in his letter to Voroshilov on the high mortality rate among soldiers and commanders.

Local medics could not reach a consensus. Some doctors believed they were dealing with a hazardous type of "toxic" influenza, others - with Japanese mosquito encephalitis. An expedition led by Zilber was dispatched to the site as a matter of urgency in May 1937.

He found out that people were predominantly sick in spring, which means that the Japanese form of encephalitis was out of the question - it was contracted in summer. In addition, only those who worked in the forest (geologists, hunters, foresters) and picked berries and nuts became infected. They did not have contact with each other and could stay isolated from the rest of the world for a long time. So the airborne flu idea did not work either.

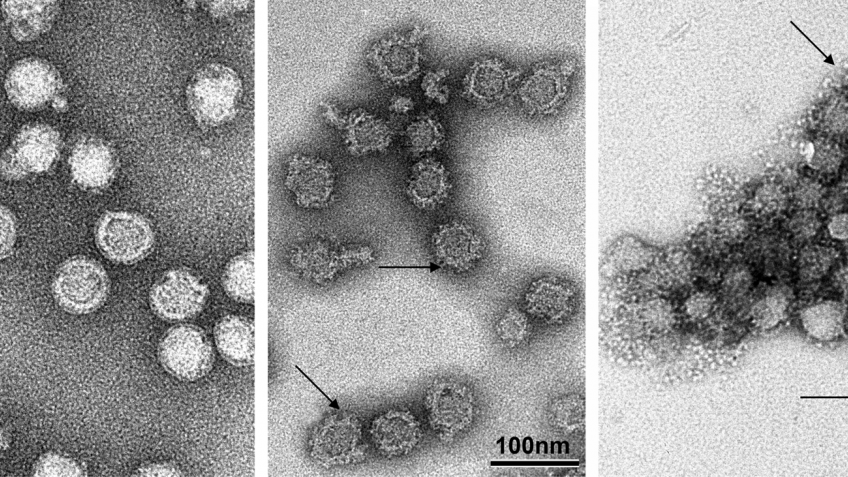

The first victim of the season, a housewife, said she had not been out of her village for two years, but she remembered finding several ticks on herself after returning from the taiga a couple of weeks ago. The scientist found the cause!

"I flew to Vladivostok to learn at least a little about ticks (I didn't understand anything about them then)... In the work of a veterinarian, I found a curve of tick bites on cows that was the same as the curve of disease increase in humans, only two weeks late. This time was the incubation period. The likelihood of the disease being transmitted this way was self-evident. I sent expedition members to the taiga to brief those working there about the danger at the end of May. Subsequently, it turned out that only one of them fell ill in 1937, although in previous years it had been the most affected group," Lev Alexandrovich recalled.

He passed on his advice to military doctors, who still advised soldiers to rinse their mouths with manganese as a reassurance.

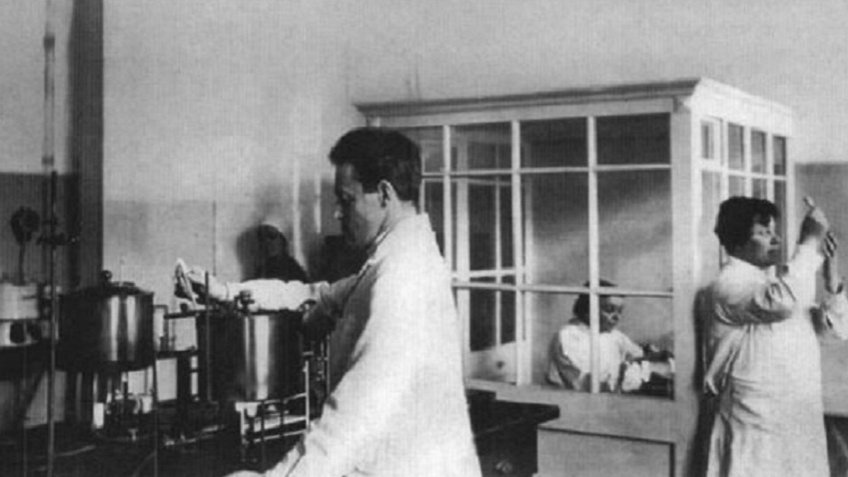

In just three months, Zilber and his expedition team established the epidemiology of the disease and its vector, isolated 29 strains of the pathogen, studied the clinic, pathological anatomy and histology. This research speed was astonishing given the conditions under which it was carried out - there were no sterile boxes, laminators, endless rubber gloves and disposable masks.

The infection of several staff members marred success. One died, a second went blind, a third went deaf and was left with a paralysed arm.

"It could not have been assumed that the virus had any particular extraordinary infectivity. After all, we were pioneers in this field; we were the first people on Earth to hold this previously unknown virus," Zilber wrote.

In August, the scientist returned to Moscow, all Soviet newspapers wrote about his victory, he was presented with awards and somewhere ahead loomed the Stalin Prize. But in November, he was arrested on a denunciation of an attempt to infect Moscow with encephalitis through the city's water supply and the slow development of a vaccine. According to Kaverin, it was the work of his brother's direct superior, the director of the Institute of Microbiology, Muzychenko. He refused to accept the material brought by the expedition, stating that the presence of viral strains within the walls of his institution was fraught with danger. The denunciation "reported" that the scientist and his assistants were poisoning wells and killing horses under the guise of fighting encephalitis, contributing to its spread, resulting in a steady rise in the number of cases and deaths. Zilber was charged with acts of sabotage and sentenced to 10 years. Walking under escort past the judges, he dropped: "Someday, the horses will laugh at your sentence."

Meanwhile, a group of scientists from the second and third expeditions to the Far East received Stalin prizes for the discoveries the scientist had made. While in prison, he wasted no time inventing a cure for pellagra, thus saving the lives of thousands of convicts dying of terrible avitaminosis.

A year and a half later, thanks to the unthinkable efforts of Veniamin Kaverin, Zinaida Ermoljeva, Zilber's ex-wife (incidentally, the creator of the Soviet version of penicillin), and his friend the writer Yury Tynyanov, the virologist was released.

Ahead of him was another arrest and refusal to work on bacteriological weapons, his release and departure into the field of cancer virology. The concept of the viral origin of tumours earned him worldwide recognition, enabling him to join the Association of American, French and Belgian Oncologists and become a member of the British Royal Society of Medicine. Lev Alexandrovich has also achieved success in his homeland: he was restored in all his rights, awarded the Stalin Prize and asked to head the Institute of Virology of the USSR Academy of Medical Sciences.

"In fundamental science, you either have to be the first or none at all", the scientist liked to repeat.