Mercury is a toxic metal, which is, however, essential for many industries. Before the late-19th century, it had been imported to Russia from Spain, with the change coming when Alexander Auerbach, a renowned mining engineer, set up mercury production. As he was the first to do so, his business was expected to be an imminent success. So how come 20 years later, he declared himself bankrupt?

There were many kings in Russia - the crystal Maltsovs, the cotton Klop, the manufactured Morozovs, the gastronomic Eliseevs, the Tiflis Armenian Alexander Mantashev was considered one of the "oil kings" of his time. They opened and bought banks, built factories, conquered the domestic market and conquered Europe. Their fortune was estimated at tens of millions of roubles, equivalent to hundreds of millions of dollars by today's standards. Alexander Auerbach was also "crowned", but unlike the above businessmen, he was more of a scientist and inventor who founded an entire industry.

Mercury has been used since ancient times in a variety of applications. Some of its uses seem very controversial today. Its compounds are still actively used in medicine, but a glass of 'silver water' was directly poured into a patient to treat constipation in ancient times. The metal was also believed to promote longevity. According to historians, the "elixir of youth" caused the deaths of several members of royal families both in Russia and abroad.

Artisans used mercury to gild metal surfaces and extract gold, platinum and silver from ores. An example of amalgamation is the coating of the copper domes of St. Isaac's Cathedral with a thin layer of gold. The chemical element was also used in the manufacture of paints, mirrors and thermometers.

By the end of the 19th century, only two countries supplied the entire world with "liquid silver": Spain, with its largest deposit Almaden, which accounted for approximately 80% of world production, and Austria. Nothing was known about "liquid silver" reserves in Russia, so it was purchased in Europe. Until mining engineer, Alexander Auerbach learned about discovering the country's first mercury ore deposit in Bakhmut county, in today's Donetsk region. The discoverer himself did not know what to do with it - he needed an expert's advice on the possible potential of the site and significant investments to rent or buy the precious land with deposits from the peasants. He got both. But first things first.

Alexander Auerbach was born in 1844 in Tver province. His grandfather owned an earthenware factory, his father was a doctor, and his mother was descended from Saratov nobles of German origin. The boy had been interested in geology since childhood, so at the age of 11, he persuaded his parents to send him to the Institute of the Corps of Mining Engineers in St Petersburg.

It was the only institution of higher learning that trained mining professionals, and it was complicated to enter. But if a young man managed to get in, good education and a brilliant career were assured. The university pupils studied core subjects such as algebra and geometry, physics, assaying, metallurgy, mining mechanics, mineralogy, economics and law. They were taught French, German and Latin, fencing and rhetoric. A lot of time was dedicated to practical studies. For example, a "mine" with underground tunnels and mines was built in the Institute's yard, and the students were trained in smelting metal at the St. Petersburg mint. This kind of education provided graduates with a good position and a handsome income.

Auerbach graduated in 1863 with the rank of lieutenant and began his career by organising coal prospecting in the Samarskaya Luka.

The young specialist spent the next few years writing his dissertation. After successfully defending his work and becoming an adjunct professor at his Institute, he was sent abroad. In Paris, Vienna and Freiberg, the young man researched celestine, labrador and topaz under the guidance of renowned western professors. It was there that Auerbach constructed his first mechanism - a goniometer with a powerful microscope, which allowed him to draw up tables of microscopic determination of minerals, unique for those times. His works were published in the "Gornyi Zhurnal" and the "Vienna Academy of Sciences".

However, his demanding professional nature did not allow Alexander Andreevich to devote himself wholly to science. Cabinet work was too quiet for him. Therefore, after returning home, he plunged into practical activities.

In those years, the so-called "coal fever" started in Russia. On behalf of the British and then French company Auerbach was in charge of exploring coal deposits in the Moscow Region, Tula and Donbas. The mining engineer was actively engaged in prospecting for minerals for private enterprises. He worked as a consultant in salt mines in Crimea and gold mining companies in Yekaterinburg and Zlatoust.

Alexander Andreevich became widely known as a talented industrialist and organiser of mining enterprises. He began to receive multiple offers to head this or that enterprise, department, even an entire region. One of them changed his life. And also the well-being of the far-flung Ural mining district - Bogoslovsky. One of them changed his life. And also the well-being of the distant Ural mining district - Bogoslovsky.

Auerbach was invited to run it by the heirs of the Tambov rich man Bashmakov, who had died prematurely and left vast areas to his relatives. The joy of such an estate was short-lived. The settlements were almost abandoned, the houses were boarded up, and the population consisted of former convicts and fugitives descendants. But there was a factor that made the mining engineer take charge of the land. They were rich in copper, considered more valuable than gold. But the local smelter looked more like a barn, and its workers were starving to death. For Auerbach, it was a challenge to match his ambitions.

Within 15 years, he turned a godforsaken place into a prosperous region.

The first thing that required development was copper production. During the first year, the volume of copper smelting increased from 17 thousand poods to 50 thousand. Indeed, it would be impossible to achieve success without improvement of techniques. Alexander Andreevich modernised the mine furnaces, installed the Becker fans, unknown in the Urals, and new refining furnaces. Although Manes' method of smelting copper matte into blister copper in retorts offered considerable wood savings compared to the previously used refractory furnace method, Auerbach noticed a drawback in the retort design during the bessemerizing of copper matte. As a result, he developed his version of the retort, making it possible to correct the deficiencies.

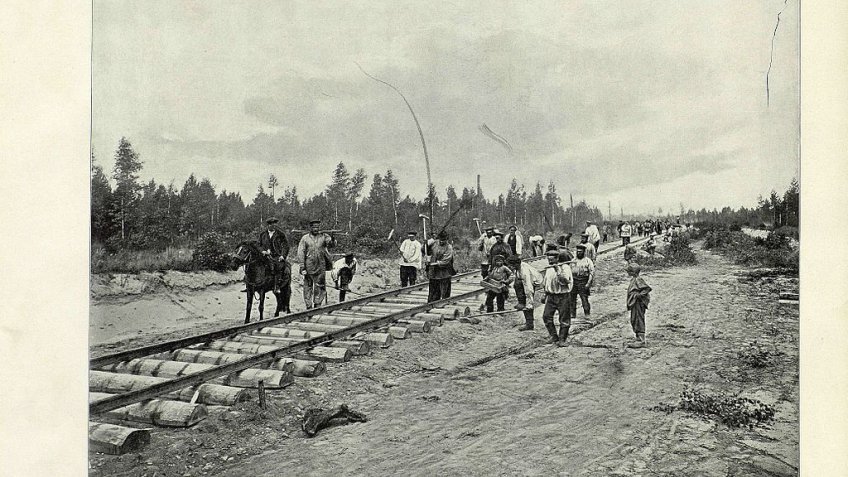

His no less significant achievement was the discovery of ironworks and a rail-rolling plant. It was made possible by developing an extensive iron ore deposit, later called Auerbachovsky, and the construction of the Siberian railway, which required a considerable amount of rails. The scientist signed a contract to deliver 6,000,000 poods of steel rails, providing Bogoslovsky District with work and a steady income for many years.

But of course, Alexander Andreevich's most crucial contribution to mining was establishing Russia's first mercury production. The deposit in Ekaterinoslav Province was found by another graduate of the Institute of the Corps of Mining Engineers, Arkady Minenkov.

In nature, mercury is rarely found in its native state, as liquid droplets on rocks. It is most commonly extracted from cinnabar. The deposits of this mineral were located on the land of peasants. Having rented them with his own money, the discoverer soon went bankrupt. The discoverer soon went bankrupt and leased the ground with his own money. He needed advice on the quality of the metal and its mining prospects from a more experienced specialist. He asked Auerbach for this advice in 1885, and he was instantly "infected" by the idea of setting up a mercury industry.

He inspected the deposit, made sure it was safe and concluded a contract with the peasants. After leaving Bogoslovsky District, Alexander Andreevich travelled with Minenkov to Spain and Austria to familiarise himself with European businesses. Upon return, he proceeded to build a plant in the Donetsk region. At the time, the annual consumption of metal in Russia did not exceed 4,000 poods.

Auerbach personally designed the plant and the mine. Moreover, he created mercury roasting furnaces having numerous advantages over their imported counterparts.

The writer Valentin Pikul dedicated his historical tale "The Mercury King" to this period of the mining engineer's life:

"The Russian market got its mercury, but the cheapness of the extraction made Auerbach think about exporting it to the European market, entering into single combat with Spanish and Austrian mercury. Access roads were extended from the plant and the mercury, insidious and seductive, like a vicious woman, flowed heavily and thickly, shimmering with false silver, abroad. Already in 1897, Alexander Andreevich received 37,600 poods of mercury.

Success! The first Russian mercury plant near Bakhmut gave him orders, honour, and a real State Councilor's rank equal to the status of a general".

If previously the country imported 4 thousand poods, now it exported 28 thousand.

However, in 1904, his luck ran out. When the war with Japan broke out, the railways were redirected to military needs. Mercury was not exported. The government ignored all the requests to allocate at least a couple of wagons. Not wanting to stop production, Auerbach paid wages to workers from his funds. The plant itself also required investments. A few months later, Alexander Auerbach declared himself bankrupt. In 1916 he passed away, only a year before the revolution, which nationalised all private companies.

The topic of the environmental and health impact of mercury has been widely discussed for years. The international discussion culminated in 2013 when the Minamata Convention on Mercury was created. Russia signed it in 2014. The document prevents the opening of new mines and gradually reduces production at old ones. From 2020, the manufacture, export and import of a wide range of mercury-containing products (electric batteries, electric switches and relays, certain types of fluorescent lamps, thermometers and pressure measuring devices) will be banned.

Scientists are engaged in research on mercury-free product manufacturing. However, alternatives are not yet technically and economically feasible in several industries. These include the nuclear power industry; the defence industry (manufacturing of detonators and guided missiles); the chemical industry related to the production of vinyl chloride (PVC), chlorine and caustic, polyurethane; medicine and pharmaceuticals; metallurgy and mining.